Russet’s eyes were still, fixed on the paper. The dichotomy in his mind was particularly vivid at the moment. In an unnerving realization, it seemed all of his thought on this topic was gushing down the darker branch. Much darker. His current chemical balances simply would not permit the thoughts. He buoyed himself out of the grim rumination. “Nope! Not at all, regrettably.”

“Oh well.” She toyed with a fancy hairbrush on the small mahogany table beside her. “I thought for sure once I met him, he’d be able to tell me something. Even inadvertently, which would help me understand all this. I thought he might recognize my locket, or something. But he doesn’t seem to know anything.”

“Maybe you are just not asking him the right questions.”

“… I haven’t asked him anything, actually,” she was embarrassed to admit.

Russet paused, shrugging off the remark. “I’ll say this about the man. He’s charged with saving me from certain pulverization. And in giving me a little more time in this mortal coil, I was able to make your acquaintance. I’ll always have that owed to him.”

“That’s true,” she said, feeling herself blushing faintly. Russet, rather innocently, made it hard to concentrate. His eye contact was the kind that could really derail a train of thought. No matter how sturdy the locomotive, it was no match for those two crisp, glacier-blue landmines on the track ahead.

What should she do in such a situation? What does one do, she’d put to herself. She’d never liked a boy before, so the playbook was as blank as one of her new sketch pads. She was forced to defer to the common wisdom on the subject, or at least her perception of it, which suggested that waiting for the male to express his feelings first was a sound guideline. In any case, it wasn’t as if (to her limited awareness) there were a lot of pizza parlors to hit up, per some formulaic stab at a “date”, even if she were inclined to take more initiative. What could she really do? It seemed doing what they were doing, staying friendly and getting to know each other, was the best and only option.

She returned to the matter at hand, which was no less confusing, but more comfortable through familiarity. At least she’d spent years thinking about it, as opposed to only a few days, as she had in the matter of romance. “Could she have been wrong?”

“Your sister, you mean?”

“Yes. Wrong about Herbert. Maybe he isn’t relevant to any of this? To knowing what the locket does, or why she died, or what we’re doing here?”

Russet leaned forward, and with some measured meaning to his voice, said, “What are you doing here, if I may ask? Aside from proving yourself a beguiling storyteller?”

She hesitated. Something else occurred to her. “That reminds. Does the name ‘Tristin’ ring a bell?”

“Tristin? I’ve never met her. Mind you I haven’t met many people.”

“No, Tristin is a guy. Sounded like a young guy. I only heard his voice. I spoke to him over a radio. He’s the one who told me about this summer camp, and told me to come here. He didn’t tell me anything about himself. He just said we’d meet when I got here. But I haven’t heard from him at all. Tristin Sheeth. You sure it doesn’t sound familiar?”

“I’m afraid I don’t know. I am proving to be a wealth of un-information, today! At least I’m consistent. Maybe if you changed your line of questioning to something dry-cleaning related? I have a whole slew of answers when it comes to getting a gravy stain out of a lace doily.”

“When I soil one of my many doilies, I’ll know who to go to.”

“Have you been practicing any of those laundering spells I taught you??” Russet became animated.

“Yes. My shirt has never felt so soft, and it smells like honeysuckle,” Beatrix said as she stroked her short sleeve. It was like the pliable ear of a newborn lamb.

Russet watched her enjoy the unlocked magnificence of her fabric. She smiled back at him as he silently puzzled over the pretty girl. An alien feeling had been gathering momentum. Was it attraction? Was this what it felt like? He’d had so little experience with girls, the feeling of falling for one was confined to his feeble efforts of speculation. The flimsy pageant played out in his mind like a Disney World parade, with no real texture or emotional gravity to anything. It was just something that happened plainly through a sequence of maudlin clichés, because it was something that was supposed to happen.

The reality of it, if this indeed was ‘it’, was more exhilarating. But also disquieting. How should he act upon it? When it came to everything else, he knew exactly how he felt. Fashion. Magic. God. Those things were resting on sturdy foundations. But this…

“Anyway, I regret I can’t be of more help. But now that you have told me these things, I would relish the chance to help you solve this riddle.”

“That would be great!”

Russet picked up the locket. “I can say with certainty at least that this is an article of magic. I think it is very powerful, but I can’t imagine what it does.”

“It’s been plaguing me for years. There is something kind of captivating about it though, isn’t there?”

“That’s a testament to its power. Much the way you probably have a similar feeling about your ring. I’ve noticed the feeling with my wand, too.” He patted the instrument’s holster. “I am convinced we will get to the bottom of this. Maybe we should consult with Grant on it? He knows a lot about these things. He taught me everything I know about magic, you know.”

“Oh?” Beatrix again felt not only guilty, but now somewhat foolish for stonewalling Grant, keeping him locked out of the fort with her opened doll. Maybe if she’d been more trusting with him, she’d have had answers sooner. “So you would like to see him now?” she asked.

“I think it’s about time we pay the old man a visit. He’s probably worried sick about me.”

“Okay. Let’s go see what he thinks.”

Russet’s mouth grew around a tremendous yawn. “How about in the morning though. It’s awfully late, and I’m beat.”

“Um… alright,” Beatrix reluctantly agreed. She wasn’t the least bit tired and was sort of itching to get going, but had to acquiesce. “Do you think we should bring Herbert along, or should we leave him out of it for now?”

There was no response, but for the low swell of a charismatic snore.

“I know you said most of the kids are gone. But if I didn’t know better,” Grant said, as he surveyed the cluttered underground lair of fort Pizzahut, “I’d say you were the only two members left.”

Daniel twiddled apprehensive fingers in the frills of his puffy shirt. “Um… do ye know better?”

Grant thought about it. “No, not really.”

“Well, ye were right. ‘Tis but the lady and m’self. Someone’s got to stay about the place and guard the treasure, after all.”

Grant was organizing a collection of small bones into orderly rows and columns. They might have been human finger bones, scattered on a dusty table. The table looked like the sliced-off top of a huge barrel. The lair’s décor on the whole was barrel-themed, as well as chest-themed, as well as anchor, rope, cannon ball, and map-themed. If Pottery Barn were run by pirates (and who knows, it might have been in Jivversport), it would have been the chief contributor to this chamber’s interior motif.

“Treasure?” Grant asked inattentively. “Would that be all the endorsement dollars collected over the years?”

“Nay. All that’s long since been swindled ‘way from us by the scurrilous Thundleshick. We’re protectin’ something far more valuable than a few doubloons.”

Grant yawned, tuning into the fact that he hadn’t slept in more than 48 hours. He shifted his knee, bumping the table, jarring the phalangial bones out of rank. He exhaled in aggravation, and set about recomposing them.

Samantha sat in a nautically-purposed net suspended from the ceiling as if it was a hammock. She was polishing off a third slice of pizza, storing excess crusts in her pocket. Nemoira was using her telescope to roll out more dough for another pie, while quietly muttering pirate-specific profanity. She was having a devil of a time with the stuffed crust spell, and was this close to giving up.

“The pizza is terrific, miss pirate lady. It is the best I’ve ever had. I’m sure my brother would agree.” Nemoira smiled and tipped her cap without turning away from her work. Samantha became sullen. “Oh, where is he? What do you think could have happened to him, mister Grant?”

Grant was startled out of a creeping slumber at the sound of his name. “I’d like to find him just as much as you, Samantha. Remember, I entrusted him with something I need back. Uh… not even to speak of the fact that he is a member of our team. No man left behind, right?”

“Isn’t it possible,” Daniel supposed, “that if ye gave him somethin’ valuable, that might a’ made him a target for some rogue?” Grant looked dismayed at the plausible notion. It hadn’t occurred to him, but then, he wasn’t used to thinking like a pirate.

“Oh no!” Samantha said. “We must save him from the rogue!”

“Now just a minute. We don’t know that.” The reassurance betrayed Grant’s own concern, though. Thoughts of scuttling, claw-clicking and small whinnies produced ominous kaleidoscopic patterns in his imagination. “Simon will be fine for a little while out there. He is an orphan, after all. He’s used to making it alone in the world, isn’t he?”

“Not without me! We always stick together. Come on, we have to go look for him now!” Samantha was out of her nautical hammock and tugging at Grant’s sleeve.

Grant said, fighting off a yawn, “Aren’t you tired?”

“No! Come on!”

“Samantha, it’s dark out there. The best hope for Simon is to wait until tomorrow. We’ll leave first thing in the morning. I promise.”

Samantha glowered at him as if he’d just run over her favorite doll with a lawnmower. “I would like my marble back, please.”

“What? Now, Samantha…”

“Please?”

It was silly, but Grant found he suddenly felt the shame of a cop being stripped of his badge and gun. He took the marble from his pocket and gave it to her.

“I’m going to go find my brother!” she said before disappearing into the cavernous hall leading up to the pizza oven door.

Grant sighed, then lumbered to the vacated hammock. He collapsed into it. “Alright. I guess we have two missing kids to find tomorrow.”

He began to doze, but was again jarred out of it by Samantha’s voice. “I am leaving a trail of bread crumbs so you can find me! And Simon too when I find him!”

Grant turned away from the voice and grumbled to himself. “Orphans…”

It was the following morning, and to Russet’s eye, Beatrix appeared to be standing upside-down and smiling. Her smile was in fact only an illusion caused by the fact that she appeared to be upside-down. It was in fact a frown. Russet was lying strewn over the side of his bed, his head and arms dangling over the edge. His glassy eyes bulged from a pasty face.

She’d had a sickening feeling she knew what to expect in his room. She woke up to discover Fort Crossnest in worse shape than ever before. Smelly, unidentifiable rubbish choked the corridors. Fluorescent bulbs flickered stuttering sentences which, in bulb language, were the equivalent to the ravings of a lunatic. Large sheets of paint peeled off the walls revealing moldy concrete. Stampedes of rats escorted even larger, less common vermin through the halls (some might have been identified by the zoologically astute as the rare whelping sewer snoogerfitch). Whatever magical forces were holding together the tidy appearance of the fort had become extinguished, and then some.

Russet’s room looked like a trailer park after taking the brunt of a tornado, one especially vindictive towards affordable blue-collar residences. The armoires were reduced to gnarled, angry chunks of splintered wood. It looked like an alien had laid eggs in the hefty armchair, and the offspring had made a savage exit before skulking into a vent somewhere to leak phlegm. The many vials of lotions and fragrances had all simply exploded. Russet was tangled in a heap of frayed, shredded bedding, breathing shallow breaths, otherwise motionless.

Beatrix’s heart sank upon encountering the scene. She managed to reconcile with the sobering reality of Russet’s crash enough to address him. “So I guess this means you’re not feeling up to seeing Grant today?”

Russet gurgled something without moving. Beatrix leaned in closer to interpret the guttural sound. “nhhrghh…”

“Huh?”

He slowly mouthed the nonexistent words. Beatrix leaned in further. “nrrr…”

“I’m sorry, Russet, I can’t…”

“Nooooooooooooooooooooooooo.”

Herbert stared at the Vend-O-Badge machine. If you looked closer, it might have resembled the stare a hit man gives to a poor slob who’s up to his neck in gambling debts and mafia loans. If you looked closer in the other direction, towards the Vend-O-Badge, you might have noticed a number of bullet-sized pockmarks in the resilient glass façade. The badge with an iconic depiction of two spiraled incisors remained pinched by the coil, taunting Herbert with its immobility.

“Herbert…” Beatrix had entered. Herbert put his finger to his lips.

“Shh. I think it’s sleeping.”

“What? The machine? How do you know?”

“I’ve got a feeling. I know how this piece of crap thinks.”

“Oh. Well, I wanted to talk to you about…”

“Hold the thought. Can you give me a hand?”

“With what?”

“Magic. I need you to get that badge for me. Like, magically, somehow.”

“Hmm.” She considered the proposition. It was plausible in theory, but then, it was quite an ornery machine. “I guess I could try to magically duplicate the snoogerfitch. Or I could have, if it were still around for me to get a good look at. What happened to it, anyway?”

“I have no idea what happened to the wretched thing. It crawled off somewhere, I guess.” Herbert gestured towards the trail of blood on the floor leading out the door. Beatrix made a troubled face at the thought of a wounded, toothless feral snoogerfitch scampering about the fort.

“What did you have in mind, then?” she asked.

“I don’t know. You’re the sorceress in training, aren’t you? Can’t you levitate it out of there or something?”

Beatrix looked at her ring, making the dubious calculations of an amateur magician. She got an idea. “How about this.” She walked to the computer station and examined the morass of archaic, dust-clogged wires. When she found one she deemed suitably useless, she yanked it out. She brought it to the Vend-O-Badge while coiling it into wide loops.

“Open it up,” she said, more like a question than an order.

Herbert was at the ready with his trusty VHS copy of Hook, which was proving to be far more useful in this newfound phase of its existence than it ever had. The slumbering machine’s wide mouth was carefully propped open. Herbert backed away and watched Beatrix with interest. She fed one end of the cord into the slot, then directed the energies of her ring inside.

The cord began to dance like a charmed snake, and slithered up towards the stubborn badge. The cord sprouted further similarities to a limbless reptile, most notably a fanged mouth with which to pry loose a badge. It struck the badge as if lunging at a succulent rodent, and descended with the prize in its mouth.

“Wow! That was so easy!” Herbert said. He admired the shimmering badge with light piercing two tiny fang holes. “I can’t believe I didn’t think of that sooner. I must be an idiot.”

Beatrix noted the gracious absence of the pronoun ‘we’ in the statement, and accepted it as a form of gratitude, knowing Herbert. “It’s a little tough to get used to, isn’t it?” she said.

“What is?” he asked.

“Magic. Or the whole ‘doing pretty much anything your imagination can come up with’ aspect of it. It makes you wonder why any of us still have problems left to solve.” She became pensive. It was the type of remark that often kick-started an inner soliloquy. Herbert wasn’t about to wait around for it.

“Hey, it all comes down to ability, just like anything else. Practice makes perfect. Those better at magic get more of what they want than those who suck. And even in a perfect world, where everyone used magic perfectly and got everything they wanted, people’s desires are always at odds. So if one guy gets everything he wants, it means some other guy is getting a raw deal because of it. There’s no such thing as a utopian society, I don’t care how many dancing monkeys or magical feather dusters or enchanted kazoos you’re packing.”

“You think so?” she asked, but the question betrayed her own agreement with the remark. On some occasions she reflected on the unexpected parallels between her own thought process and Herbert’s. She’d always considered cynicism and pragmatism to be cornerstones of her worldview. But Herbert seemed to take it to a different level.

“Yeah. Absolutely. Anyway, speaking of getting things we want… How about you get us some more badges with your cool snake trick? If Thundleshick thinks three badges are impressive, wait ‘til he sees, like, fifty.”

As the lively cord-snake went on an all-you-can-bite badge spree, Beatrix presented a casual change in subject. “So, I’m going to go see Grant today. To get Russet’s medication.”

“Whoa, check these ones out!” Herbert was like a kid in a candy store, fixated on the windfall of vibrant badges. He ogled one bearing an iconic depiction of a unicorn with musical notes levitating from its open mouth.

She continued. “I’ll be taking the doll to find him, wherever he is.”

Herbert remained engrossed. He felt like he’d found a way to crack a Vegas slot machine. “Okay.”

“I guess you’re going to see Thundleshick with all these badges, then?”

“That’s the plan. Carmen told me how to get to his castle. Speaking of which, she’s made herself scarce lately. Wonder what she spends all day doing in this dull place…”

“I was sort of wondering that myself. Anyway, I imagine it’ll be a long hike to his castle. I was thinking we could do something like this. I’ll go get the medicine and come right back. Then you could take the… well, one of the sub-dolls, for lack of a better word. That way you could instantly travel back here. It might come in handy if you get into trouble.”

“That sounds…” Herbert was mystifying over a badge bearing a crank-operated wire whisk, and a plump udder. “That sounds like a pretty good idea.”

Herbert cradled the heap of badges to his chest and beamed with the pride of a new father. “Thanks a lot, Beatrix. That was awesome. It’s amazing none of those idiot campers ever thought to do something like this.”

“Maybe there was some kind of code of conduct against it. Like a scout’s honor thing. Or maybe they were just afraid of having their hands chewed off.”

With that, the copy of Hook cracked, disintegrating into plastic bits as the slot snapped shut. The machine was briefly agitated, but quickly settled back into the dull purr of its slumber.

“So…” Herbert asked conversationally. “How is Russet, anyway?”

If there were invisible elastic bands holding up her facial expression, it was as if they’d suddenly been cut.

Herbert watched the doll, formerly red and held by Beatrix, now blue and hovering in midair. It fell onto her bed.

He slouched onto the bed next to the freshly-teleported doll. It seemed to him as if it should be emanating steam from the trans-dimensional journey, maybe like the DeLorean from Back to the Future does just after Marty gets back from dicking around with his parents’ prom in the 1950s. He looked around uncomfortably. He’d never seen Beatrix’s room, and it was an odd feeling being left there by himself. She was such a private person, he couldn’t imagine she would be thrilled leaving anyone alone with her stuff. This, more than anything, told him that she did not intend to be gone long. Maybe a few seconds, even.

He’d had no intention of snooping in any case. Snooping in a girl’s room struck him as a low-reward, high-risk scenario. On the one hand, you might find exciting artifacts quite mysterious to the male universe, such as peculiar clasps and instruments for channeling long hair in certain ways, or cryptic products for which absorbency is a touted virtue. Herbert just wasn’t interested. But when it came to articles in plain view, he thought it was hard to classify those items as contraband. In the same way that it was a stretch to say that scooting down the bed a couple feet to get a better look at them could be considered snooping.

Herbert was surprised to see the doodles. But to be fair, he was surprised at the very notion of artistic inclination in any human being. It might even be speculated that his curmudgeonly lack of creativity could be to blame for his impotence with magic. Unfortunately, Herbert wasn’t quite creative enough to make this postulation himself.

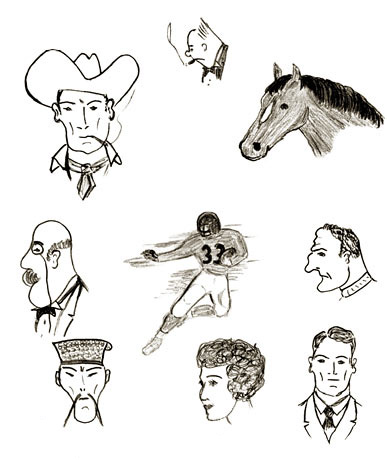

The more he looked, the more he found the sketches charming. There was something innocent and unassuming about them. They were the byproduct of a quiet, idle girl simply trying to pass the time, not meant for any kind of consumption outside her own. Though each drawing was scattered haphazardly on the pages and seemingly unrelated to each other, Herbert found they all told a story together. It was a tale of a dashing boy with a gun and an eye patch, his trusting subordinates, and a myriad of whimsical creatures for them to study, tame, conquer, and in all likelihood, slaughter, for the bountiful riches and magical lore they might supply. Herbert smirked as he turned the page.

But on this page, the story took an abrupt and disturbing turn.

It was not a drawing at all. It was a black and white photocopied image of himself, mingling with text. It plainly listed personal information about him, such as his blond hair color and blue eye color, and some less complete information, such as his unknown date of birth, his unknown social security number, and his unknown place of residence. Herbert felt his fist tighten around the crinkling piece of paper.

“Beatrix…” he hissed, again invoking his Seinfeld-angry-with-Newman impression.

He didn’t know what this document meant, or why exactly it made him mad, but he was certain that she was being dishonest with him from the start. And the more his fist tightened and the more he paced the room, the more dishonest she became in his mind. He stopped and stared at the doll on the bed.

“Alright, you want me to take one of these dolls? You got it.” He opened the blue doll. He then removed the smaller doll inside, and as he’d seen Beatrix do before, split it into an identical red doll and blue doll. He put the drawings and the document back on the small table, along with the newly-created red doll. He pocketed the blue doll, and left the two halves of its larger parent lying on the bed.

He left the room, and proceeded to the lowest point in the fort, per Carmen’s instructions. Уровень 37. Nobody knew what that meant, or how to pronounce it.

With the sunrise over Jivversport, the ludicrous hidden bird population cracked the silence. Samantha watched the cobblestones as they passed beneath her. Her weary face relaxed into a more satisfied expression. There was one. Then another. She’d recognize that trail anywhere. Those were Simon’s bread crusts.

What did she tell him? Keep a spare crust in reserve at all times, in case of emergencies. She felt proud of her younger brother.

The trail led her into the cellar of a deteriorating, sinking stone building. Simon’s tenacity in maintaining the trail surprised her. She sloshed through the black water of the murky catacombs, but became silent when she heard voices ahead. She crouched behind something that looked like a crumbling, bearded statue.

Terence shot a humorless glance towards Simon. “The pieces cannot move backwards.”

“Uh-huh! It can when it is a king!” Simon said, leaning forward to make his move. The rope tethering him to a statue tightened in resistance.

“That is not a king. A beetle used to king one of my pieces recently crawled on to one of yours,” Terence explained. It did not sound like the first such explanation in the course of the game.

“Really? Which one?”

“That one there. The curled up grub.”

“That was your grub? I thought it was mine!”

Terence exhaled over the checkerboard drawn onto the floor with a piece of white stone. It was frustrating enough handling a hyperactive orphan boy without also having to manage the ambiguities of a game played with an assortment of stones, grubs, and lethargic beetles. In retrospect, the whole exercise seemed incredibly stupid, since he could have just magically created a fine checkerboard set. However, Simon’s enthusiasm in gathering up the ingredients for street checkers had preempted the thought.

Samantha breathed harder at the sight of her captive brother. She removed the shiny marble from her pocket, and lobbed it into the darkness behind the crustacean guard. Clicks echoed from unseen stonework.

Terence about-faced with a terse snort. “I’ll be right back. Do not move the game pieces. I will know if they are different.”

“What if they move by themselves?”

Terence scuttled away to investigate. Simon shrugged, and mindlessly picked up a beetle and some sort of larval cocoon. He crashed them together as if they were kamikaze aircraft. “Pchoo, pchoo! Pshhh! Pow, pchoo! Pch—huh?”

“Shh! Keep quiet, Simon!” Samantha whispered as she untied the rope.

“Hi, sis! You found my crusts! Hey, do you want to play a game with me and mister horsey crab?”

“No, Simon. We have to go. Don’t you realize you’ve been captured by a rogue?”

“A rogue?”

“Yes! Now hurry, before he sees us!”

“Okay. But first I have to get something. It belongs to mister Grant.” Simon squirmed out of the loosened rope. He grabbed the red doll.

The two children froze at the terrible sound rumbling from the darkness. It sounded like a deep, brooding whinny. Samantha grabbed Simon’s shirt collar. “Run!”

“Why can’t orphans leave behind a sensible trail?” Grant lamented. “Like fixed markers. An arrow drawn on a wall, or string tied to a post. Anything that doesn’t get blown around by the wind or eaten by birds would be fine.”

Grant scoured the pavement for signs of a dwindling trail, cursing his orphan tracking abilities. His nautical partners supplied little help. “Is that a crust there, mate?” Daniel said, spotting a fleck of white near a gutter.

“I think it’s just a pebble,” said Grant, who suddenly sprinted towards a flock of bobbing pigeons. “Hey! Shoo! Get away from that bread!” The feathered pack of diseased creatures scattered into the air. Grant found the vacated pavement empty.

He threw up his hands. “Where would you guys be if you were a couple of lost orphans?”

“Couldn’t say, mate. Ye can be sure though there’re more places to get lost beneath the streets than above.”

“I was afraid of that. So do you have a map of this place I can look at?”

Daniel made a face like he’d just walked in on his own surprise party. It was one topic sure to get a pirate fired up, sort of like asking an avid stamp collector if he happened to have anything kind of interesting or unusual that one might put on an envelope. “Do I have maps, ye ask? Do I ev…”

“What’s she looking at?” Grant cut him off. Nemoira was looking through her telescope down an empty street. She lowered it from her eye.

“Do you see something?” asked Grant.

Her gaze was fixed. “Regrettably, you may have what you’re looking for soon.”

“What do you mean?” Grant walked to her vantage, and saw nothing. A crestfallen Daniel was putting rolls of yellowed maps back into his satchel.

The ground shook. At the end of the empty street, smoke rose from the source of the explosion. Dust from the ancient buildings around them was shaken loose, sprinkling gently on the ground. The glass storefront to a Coldstone Creamery® shattered.

Grant looked at Nemoira decisively. “This way, then.”

A four story brownstone building sailed upward like a rocket, riding above its trail of crumbling brick, ash, and fire. It reversed direction and plummeted. It crushed the hood of a vacant gas station, disintegrating into a textured cloud of gray. The blast knocked the orphans to the ground. They picked themselves up and resumed their frantic flight.

Terence scuttled with a terrific velocity for such a small creature, much the way the speed of an ant is considered tremendous when scale is taken into account. He walked up walls, across roofs, and underneath awnings upside-down. One claw opened, cradling a swelling ball of fire. The projectile obliterated a building placed in his path. His red eyes momentarily wandered into the sky as a flock of birds decided a different preening location might be in order. As he did so, the upper half of a museum was sawed off diagonally by ocular lasers. The ornate roof slid down the sliced slope, then collapsed into the structure beneath.

“We’ve done it now, Samantha,” Simon huffed. “I should have stayed to finish the game with the horsey. Now he’s mad!”

“Keep… (huff…) running… (huff…) I told you he was a… (huff…) rogue!”

Behind them, a high-pitched noise grew to a crescendo. It was an otherworldly neigh, the kind you’d expect from the great black steed mounted by a warlord commanding an unholy army. Windows exploded from the sonic assault. The façade to a stretch of row houses leaned forward under its brunt.

Samantha skidded to a stop in front of an alleyway entrance. “Simon, turn here!”

The children bounded through the winding alleys, dipping into cellar windows, out back doors, down sewer grates, and up to the street again. These were the standard alleyway evasion tactics of a practiced street urchin. They took to it as if fleeing from a red-faced vendor after pilfering a loaf of bread. Terence’s path of destruction was inexorable, though. They knew soon there’d be no alleys left through which to wend.

Simon and his burning lungs were about to complain to his sister, when he felt something jostle in his hand. It was the doll. It twitched, and then again. He dropped the doll to the floor of the dim alley. “Oh, no! Samantha, help! I need to protect that!”

Samantha looked up at the tall walls squeezing the alley, feeling no more confident in their permanence than if they were theater props. “Forget about it, won’t you? Let’s go!”

Simon opened his mouth. The doll was no longer red. Nor was it on the ground. It was now blue, and cupped in Beatrix’s hands. She stood there processing her new surroundings. And her new company.

“Simon?” she said.

“Beatrix! It is you! I knew it!”

Samantha’s disbelieving eyes showed signs of tears. She ran to Beatrix and hugged her around the waist. “We knew you’d come to save us.”

“Um…” Beatrix started, nonplussed. “I’m happy to see you guys too. But what the heck are you doing here?”

“We’re running away from the horsey crab rogue,” answered Simon.

“The what?”

“Yes, we have to go now. He is ruining the village, and he is very dangerous!” Samantha warned.

It did seem there were signs of trouble. There was a sulfurous smell in the hazy alley. There was a growing rumbling, as though they stood over a subway train rolling beneath. She couldn’t have known it was the sound of structurally weakened buildings collapsing nearby. And she couldn’t have known that the source of this destruction was now clicking through the alley towards them. It stood no higher than her shins.

“What’s that?” Beatrix asked, with understandable innocence.

“That’s him! Oh, Beatrix, please! We should run away!” warned Samantha.

“Really? It doesn’t look that dangerous,” she said, but instantly felt foolish for blundering onto such famous last words.

“He is chasing me, Beatrix!” Simon pulled at her garments.

“No, son,” Terence said. “You have nothing to worry about. I’m not chasing you any longer. I am chasing her.” His eyes glowed like red laser pointers in the direction of Beatrix. She inched backwards.

“Oh crap.”

Herbert took a final moment to look around before climbing down the iron ladder into dark well. The chamber was enormous, enclosed by smooth concrete walls curving to form a domed ceiling. The concrete was tinted with layers of caked-on muck, perhaps a kind of algae. The saturation of muck ended at a blurry horizontal line several dozen feet above the floor. To Herbert, this was evidence that the chamber had been filled with water. Above this line was a label in very large, faded lettering which said “Уровень 37”. Herbert couldn’t read Cyrillic, but presumed the word roughly translated to “level”.

He held the hand rail, and backed on to the iron ladder. The pillowcase tied to his holster swung behind him and dangled into the darkness. Inside was a flashlight, a bottle of orange soda, an assortment of dubiously-gotten merit badges, and a crude map to Thundleshick’s castle based on Carmen’s instructions. In his right pocket was the blue sub-doll.

His metallic footsteps echoed against the mossy, dripping stones.

Between gasps, Grant mentally cursed his decision to leave the doll with Simon. He cursed thinking it was a good idea to let it out of his sight. And for that matter (after pausing for another gasp), he cursed allowing that crafty girl to elude him in the first place. He wasn’t sure why his thoughts were being staggered by his struggle for oxygen. Maybe in truth, his mind was out of breath too.

He turned a corner, adjusting his course towards another loud explosion. The pirate counselors kept pace behind him, their fancy metal accessories jangling in their loose clothing with each step.

“Been waitin’ on this for years,” Daniel said with a challenging grin. “High time these Slurpenook scalawags took to our streets for a proper showdown. Their skulkery in shadows has turned my stomach, no less’n the choppy waters of monsoon season.”

As he jogged, Grant marveled at the bottomless supply of nautical aphorisms and “Piratese” peppered throughout Daniel’s casual parlance. Was there a handbook on it somewhere? Daniel unsheathed his shiny dagger and waved it at the sky. Nemoira glanced to her side.

“Daniel, will you please put that away?” she said.

“Nonsense! Best prepare ye for battle, woman. It looks to me as if the villains’re taking us across the south side. If we head for town square, we’d surely cut em’ off!”

Daniel flicked a long braid over his shoulder and blazed a trail into a crooked alley between storefronts.

BANG.

Herbert shut his eye and made a face like he was popping his ears. He hadn’t expected the gunshot to be quite so loud. It seemed the noise had ricocheted around the cramped space bound by the walls of the subterranean cave.

He gave the limp creature a little kick. Its prickly torso and flaccid bat wings tumbled end-over-end down into a narrow underground stream. He shined his flashlight on it. Were those corkscrew teeth? He sighed. They even had a little serration. He thought if one were inclined, it wouldn’t be too difficult to round up an assortment of indigenous animals and cobble together an exceptionally diverse Swiss army knife using the prodigious dental yield.

He pointed the flashlight at the path ahead of him, and tapped it when it flickered. It was supposedly a magic flashlight, since it was retrieved from the same cardboard box of mesmerizing wonders from which he obtained his gun. Maybe the thing was horribly potent. A sort of battery-operated portal for ruthless demigods, the one final piece critical to a cruel magician’s sinister ambition. But Herbert would be damned if he was going to coax any grim enchantments out of the mystical Black & Decker.

It wouldn’t be long now before he’d reach a critical juncture on his map. One or two miles, perhaps. What did that say? The things that came from Carmen’s fancy peacock feather quill pen were almost as difficult to solve as the things that came from her mouth. They looked like initials.

Ahead, there was an indistinct flapping. The flapping was leathery, like several pairs of flimsy bat wings producing the commotion of haphazard flight. Herbert reached into the pillowcase and retrieved two merit badges. He wadded them up, and shoved one in each ear.

BANG.

BANG.

If Jivversport was dense with the decay of commercial enterprise, then town square was the jewel of economic depression in its crown. Storefronts packed themselves tightly among each other like boxes in an overcrowded warehouse. Some seemed practically inserted into rectangular grooves carved out of ancient, likely historic stone buildings, through either lapse in zoning protocol, or the greed of corrupt civic administrators. Or maybe the venerated artisans centuries ago had intended all along for a Bath and Body Works® to occupy their baroque stone carvings.

Missing letters punctuated the signs of otherwise easily recognized franchises. Cr//te & Bar//el®, Old Na//y®, Tac// Be//l®, to name a few, which by sheer coincidence, were once the frequent shopping haunts of pirate-types. The first two for obvious reasons, to service nautically-themed décor and apparel needs, and the latter-most of course to cater to the legendary zeal for Mexican food shared by all rugged seafarers.

It was quiet. Over distant rooftops, black smoke pooled into the sky, like ink drops into a glass of water, upside-down. Town hall loomed over the square, menacing in its great stature, and in its abundance of gothic fixtures. It seemed to be weighed down by gargoyles and statuary, like a crazy man’s coat with too many strange trinkets affixed to it. Grant strained to view the top of the spire. Atop it was a statue of a man in a suit.

The face of the building erupted. An enormous twisted metal javelin punctured it from within, and exited its stone and glass chest. The mangled piece of rollercoaster track thundered into town square, smashing the non-functional fountain. It halted, still enough for Grant and the counselors to see its car still intact and affixed to it, and the Batman emblems decorating the ride.

The rest of the building came down.

The party maneuvered in time to evade the tipping spire and its statue. The spire was demolished on the cobblestones, making a sound like a huge payload of porcelain dishware hitting the ground. The statue too was shattered. Grant, crouching against the cloud of dust, could make out a centuries-warn engraving on its base. It was an eagle, and the letters “//o//al////////aga//”. Grant began to wonder if anything in this village was spelled in its entirety.

Through the dust-choked void left by town hall, three unimposing figures fled into the square, stumbling over the stones with all the grace of baby waterfowl. Daniel and Nemoira readied their weapons, but eased their grips. It was the orphans, followed by a taller, slender girl.

Beatrix’s expression of surprise matched Grant’s, though amplified through the adrenaline of flight. “There you are!” she said, winded.

“Beatrix…” he said. “I see you’ve figured out the doll, finally.”

Through her look of urgency, there was a hint of culpability. She couldn’t tell if he was being sarcastic, or just naïve. “Oh. Yeah, I guess I got the hang of it.”

“What the hell is going on here?” he asked, preemptively gripping his sword’s hilt.

“I’ve come back to tell you I found your friend. But that can obviously wait. We really should get out of here.”

“Who?” Grant said absentmindedly. “Oh, right, right. Russet. How is he?”

“Grant, the pirate was right,” Samantha spoke up. “Simon was kidnapped by a rogue! I helped him escape, but now he’s furious with us. We have to go!”

“Uh-huh!” Simon affirmed, as if vouching for something by which he’d sworn all his life, such as a quality panhandling mug, or a reliable brand of bootblacking brush.

“A rogue?” Grant’s sword was already unsheathed. “You mean the little horse-thing?”

“Yes!” Simon said. “But he does not make a small whinny at all. I would say he makes a very big whinny.”

“None of this matters.” Beatrix had decided to take charge. “Everybody come here and touch the doll, quickly. It’s time to go.” Her hands shook as she prepared to operate the doll. But then it was gone. It was riding a small, hot projectile, whipping this way and that until settling into the town hall’s remains.

Through the fog of demolished architecture, there was something crawling over the rubble into the square. It was the least imposing form yet.

Herbert waded out of the knee-deep water onto a dry landing of rock at the foot of a staircase. He climbed the stairs. There was an open doorway in the rock wall facing him. A hanging lantern flickered the shape of the doorway on to the ground with warm light.

With his hand on his sidearm, he passed through the door and found himself looking up right away. There was another metal ladder, this one of studier construction. It traveled up a small tunnel a great distance. To the side of the ladder was another door, just as rugged-looking as the one he’d passed through. Adjacent to both doors was an old wooden sign with hand-carved letters.

◄ F.C.

► T.C.

▲ W.H.

The left arrow pointed in the direction he came from, so he presumed it stood for “Fort Crossnest”. He gathered “Thundleshick’s Castle” was to the right. This guess was reinforced by the fact that climbing a ladder was not in Carmen’s instructions. Progressing through the other door seemed like the logical choice.

The “W.H.” left him unsettled, though. On another occasion, he might have chalked up to coincidence the fact that the letters were also his initials. But given recent events, not the least of which was discovering the unusual video recording, he wasn’t sure what to think about it.

Cool, musty air poured from the vertical tunnel. Something was drawing him up there. He didn’t know if it was mere curiosity, or something more insidious. He started to feel ill at the thought of what might be up there. Maybe it was inevitable. It might be his inescapable peril. Or worse yet, it might hold his destiny—a threshold to even grander adventures.

Without dwelling on it for another moment, he headed through the door, towards “T.C.” If all went according to plan, adventure would be a thing of the past. A blemish on an otherwise spotless record, nothing more.

“It’s just as I told ye. A wretched Slurpenook agent. He’s probably after our heads for a new badge from his dark master. Mark my words!” Daniel flailed his silver dagger and made as if to charge the creature. Nemoira restrained him by the loose end of a colorful kerchief.

Terence rolled his eyes. “Yes, that’s what I want. A merit badge. All glory to Fort Slurpenook and whatnot. You there, pirate boy. Do I look like an imbecile to you?”

Daniel wasn’t sure how to respond.

Terence proceeded. “All of you disperse. There’s no need to bring harm to yourselves. I’ll have a few words with the girl, and that’s all.”

“The problem is,” Grant summoned his most nonchalant voice. “I owe her one, so I can’t let that happen. Also, you’ll have to pardon me if I suspect you have more in mind than polite conversation.”

He had the look of one who wasn’t going to hold anything back this time. He had a feeling he couldn’t afford to.

He raised the sword, now burning as if being tempered by a blacksmith. The huge broken stones from the town hall rose into the air at once, levitating and spreading to fill space evenly. They too began to glow bright red, as their hard edges softened, appearing gelatinous. Each stone soon became a globule of molten rock, trimmed with fire. With one motion, Grant brought the full volley towards the tiny target.

Terence’s deceptively nimble claws deflected each piece towards the skeletal remains of town hall, reconstructing the building out of red-hot bricks. The building stood strikingly similar to the way it had before, though now smoldering at hundreds of degrees, and wobbling under the suspect rigidity of molten rock. The building sagged as it cooled. The final missiles, the blazing statue bits, were reassembled and carefully positioned on top of the spire.

As Terence was distracted with the process, like crowning a Christmas tree with an angel, Grant brought his sword down on the small adversary. The furious finishing move, however, was halted; the sword was immobile between pinching claws, as if stuck in stone.

Grant felt his internal organs rattle from the concussive force. He flew backwards through the air, riding the front of a mighty sonic neigh.

“Sam, Simon! Help me find it! Hurry!” Beatrix and the orphans scurried to retrieve the doll in the fresh absence of the cluttering debris.

At a distance from the fray, Daniel’s dagger quivered in his hand. They were not the jitters of fear, but of resolution.

“What are you doing?” Nemoira asked. But she already knew. Her expression pleaded with him to reconsider.

“Lass, there comes a time when a man’s got cause to leave his blood on the deck.” His dagger traced steady, wide circles in the air. “Ye’ll understand, one day.”

The sky condensed with swirling, black clouds, flickering with sporadic pockets of lightning. The black whirlpool spread, projecting darkness onto the melee below. The combatants paused, craning upward at the development. Something lurched from the eye of the dark storm, something large, like a ghost ship emerging from fog. It was a great trident, maybe the one wielded by Neptune himself.

The trident stopped. It slowly retracted itself, back into the darkness. Just like that, the clouds dissipated.

There were two small holes in Daniel’s forehead. Piercing the holes were two steady beams of red light. The lasers traced back to their sources, each from a small horse nostril. Daniel’s eyes rolled up, revealing white. He pitched backwards, dead.

Nemoira’s cheeks were already wet. She sank next to the body, and covered his eyes.

“I got it!” Samantha yelled, waving the doll.

“Good work!” Beatrix said, rejoining Samantha. “Everyone, gather around the doll, quickly.”

Grant lumbered to his feet. Each organ felt like it was individually masticated by a large herbivore, and then sewn back into his torso. He hobbled towards Beatrix, but the hobble became an urgent sprint. He dove, knocking her to the ground. The flaming, severed head of the town hall statue scorched past them, detonating moments later.

He looked at her through a pained grimace, though his eyes nevertheless appeared to be asking politely if she was alright.

“Thanks,” she said. “I’m okay. Here, let’s go already.” She held out the doll. The hands of Grant, Simon, Samantha and Nemoira all found the doll. Beatrix twisted it.

Her lower lip dropped a bit.

She twisted it again. And again.

“Herbert!” she hissed, unwittingly invoking her own Seinfeld impression.

It had been hours since he’d removed the doll from its mother, and its red sibling, so to speak. Herbert held the glossy blue item as he plodded up the absurd quantity of stairs.

He felt guilty. Maybe Beatrix had a good reason for the deception. Whatever she was up to, perhaps it didn’t warrant being stranded indefinitely with some guy named Grant. After all, wasn’t she only trying to help Russet? It was more than he could say he’d ever try to do.

The stairs were shallow, and offered generous room for the feet. He noted what they lacked in height, they made up for in contributing to the most gratuitously long staircase in the universe. The stairs spiraled lazily and gradually upward, presumably to the surface where he would find the castle. He’d already been walking for miles, all upstairs. He was soaked in sweat, and had left the empty orange soda bottle littered somewhere around mile two.

He looked at the doll again. He considered for a moment returning with it and putting it back together.

But he’d come too far already. And soon he’d be home.

As he thought this, daylight ahead greeted him. The closer he came to the opening, the more he could make out what looked to be the forms of a castle. Though it seemed the forms were bleary, and somehow unaccountable for how they were attached to the larger structure. Maybe it was just a foggy day.

Though he was tapping one of his little exoskeletal legs on a cobblestone, Terence’s demeanor was otherwise patient. He wore a big smile on his elastic horse face.

His audience looked wholly defeated, with the exception of Simon, who was distracted by a lame pigeon bobbing around in circles nearby.

Terence’s claw became malleable and soft, and bloated into a plump tentacle, complete with suction cups. It wrapped around Beatrix’s neck, and lifted her wriggling body into the air. Grant felt for his missing sword, no longer in its sheath. Nemoira extended her telescope. It shimmered with magic as she readied herself to wield it like a baseball bat.

Terence’s smile dissolved. Short puffs from his nose became longer, deeper. Soon little streams of sulfurous vapor spilled from them, and the puffs were accented by clouds of flame. Nemoira’s grip loosened around her weapon. Her posture slackened. She knew they were goners.

A singsongy, metallic voice broke the atmosphere of impending demise.

“Tender me answers, or those of their ilk,”

“To the riddle I’ve sung, should you give it a listen!”

The puzzled group looked around. Terence sniffed back and forth. There was no one to be found nearby. He again focused on his captives, drawing a deep, almost serene breath.

He released a great cloud of nasally-produced fire. But as quickly as it expanded, destined to engulf the party, it had shrunk into nothing. It was sucked into a small point a few yards from Terence, close to the ground, swallowed.

Swallowed, literally, by a hefty can of soup with a jagged mouth and eyes. Pleased with itself, the can embraced the self-conscious posture of a thespian.

“Tender meat bathed in an ocean of milk,”

“The soft portions sprung from its carapace prison,”

“They temptingly swim, slathed in buttery silk,”

“Rescued by spoon should the need be arisen!”

Grant coughed. He wiped a few drops of blood onto his sleeve. Nobody spoke. Aside from Simon’s silly smile of gradually dawning recognition, the scene resembled a dining party which, upon receiving the bill, found it to contain not a tabulation of menu items, but an array of crudely scribbled phalluses.

“Mister Soup!” Simon waved.

“Yes, undersized man? What is the answer is what you would care to supply me with?”

“Lofthter… fithk,” said the voice from above, currently being strangled by a tentacle. Lentil repostured himself so his eyes pointed upward.

“Yes, what was that? What solution is it you wish to give is what you…”

She interrupted, loosening the grip of the slimy collar, raising her head up. “Is it… lobster bisque??”

Lentil’s face scrunched with delight. He began a self-satisfied jig.

“Uh… was she right?” asked Grant. A small huff came from Terence’s mouth, which was hanging wide open.

It was so fast, they could barely follow it. Maybe only a flash from the can’s metal reflecting the sunlight. The tentacle was severed by a razor-sharp mouth. Beatrix fell, choking. The cylinder, midair, flipped and came down hard on the small, recently amputated creature. He stomped on Terence repeatedly. Terence protested, muttering at the unintelligent pest.

CLONK CLONK CLONK.

“Chilis of fury, chipotles of doom!”

“Stop.”

“Bring scalds to the tongue, pains that you’ll hope-end!”

“No more rhymes about… ow… soup, please.”

“It fills me with worry you’ll have to consume…”

“Relent with this idiocy at once.”

“This can of five-alarm whoopass you’ve opened!”

“OW.”

CLONK CLONK CLONK.

Lentil halted his clonking assault, and focused his eyes as if narrowing upon a bee that had landed on his nonexistent nose. If being cross-eyed made him appear any less dignified, it was only by a smidgeon.

The air in front of his face warped, like a spatial pinch. And then he released it, along with some magnificent pent-up magical energy with a POP.

The small lobster-form hurtled miles through the air, towards a distant mountain range. Everyone sat in silence, watching the dumb can.

Part 4

Herbert didn’t know what to make of what he was looking at. It was recognized as a castle easily enough, in the same way that if you viewed one through a prism, you’d likely be able to guess it was a castle. A spire floating here, an archway drifting there, a winding stone staircase meandering over there—the astute ear can tell when a building is attempting to speak Castlish, even if the structure itself seems far from fluent in the tongue.

However one decided to categorize the thing, it was vast, and somewhat nauseating for Herbert to look at. He monitored a particularly active tower looming above. There was no clear way it connected with the rest of the structure, save a bit of indistinct stonework boasting dubious spatial properties. It lurched forward, tipping slowly, as if destined to fall forward. It then quietly disappeared, as if dissolving into space. Numerous (literally) flying buttresses jockeyed to fill its place.

The only features that appeared to be stationary, luckily, were the grand doors of the front entrance. If this building could be said to have a formal “front”, that is. Locating the front was a task similar to identifying the corner of the Oval Office (a challenge which some former presidents would have their less intelligent visiting diplomats undertake).

Herbert went in.

The streets of Jivversport had regained their characteristic void of activity. All was silent but for the footsteps of a beleaguered troop, and a metallic clonking on cobblestones bringing up the rear.

Beatrix looked to her side at the pirate counselor. She’d been leading them through the streets, but had barely said a word since the catastrophic town square melee.

“Maybe we should say something to her,” Beatrix said softly to Grant, who walked on her other side. “She looks miserable about losing her friend.”

“Maybe.” He thought a moment. “But I’m pretty sure that’s how she always is.”

“It’s okay,” Nemoira said. “I’m not upset about Daniel.”

“Oh?” Beatrix said.

“It’s fine.” She cracked a faint smile. It might as well have been an eruption of euphoria by contrast. “I know where he is.”

“Miss Pirate?” Simon said, while channeling every ounce of his orphan resolve into the task of avoiding the gaps between cobblestones. “Where are we going?”

“If we’re to get to Fort Crossnest, by sea is the fastest way.”

“Yay!”

This was news to the others as well, but then, they wondered why it should be. What other means of travel would a pirate be likely to offer, or anyone, for that matter, who was in the process of leading them to the town’s seaport?

Dormant hulks of metal and wood littered the shallow waters. Conspicuous among them, even before Nemoira guided them to it, was a smaller vessel, burdened with an overabundance of colorful sales. What The Rubicund Wayfare lacked in certification from a competent maritime engineer, it made up for with the nod from an eccentric interior decorator.

They boarded the ship.

Thundleshick’s castle wasn’t the type of place you wanted to get lost in. Luckily for Herbert, his short, knuckle-dragging guide led the way through rambling halls with an earnest diligence, if also a gruff temperament.

Upon entering the castle, he’d been met with a grand hall. Grand was just a word affixed to it though, much the way any lower-income household technically possessed a master bedroom. It sort of resembled Count Dracula’s gothic, capaciously-built sewer. Lounging about were several dozen monkey bellhops. Their little red vests and hats were, putting it kindly, gloriously unlaundered. Through the shrill hoots of primal intimidation, one monkey calmly separated itself from the pack and gestured for Herbert to follow.

As the simian led Herbert on what had proved to be the beginnings of an epic journey through the dark, pungent halls, he had to wonder. Had Thundleshick been expecting him? Had he appointed this taciturn, mite-ridden sentry to lead Herbert to him? What plot was the perverse old bastard hatching now?

The monkey slowed, then planted himself with the stoic discipline of the Queen’s personal guard. It raised its furry paw and pointed. Herbert looked into the dark corner he was being shown, squinting to make it out. There was a lump. A very smelly, dark lump, of not-so-mysterious origin. It was a pile of fresh primate feces, one over which the small ape had clearly invested some amount of personal importance.

Herbert slouched. He supposed, now that he was officially lost, he’d have to find the campmaster himself. All wasn’t hopeless, though. For starters, he could follow the odor that smelled even worse than the monkey shit.

The salty breeze was refreshing. It whipped Beatrix’s long hair about as she looked into the abnormally blue sky. Impossibly puffy clouds levitated, not high above the ocean. They all occupied distinct shapes, doing the lion’s share of the work for the daydreaming sky-gazer. One of them looked like a white sculpture of a bearded southern gentleman holding a pale and corralling poultry. Another was a giant wearing a tunic of leaves, lovingly tending to a field of produce. And yet another was a smiling cherubic man holding what looked to be a small grill. The man was either Buddha, or possibly former heavyweight boxer George Foreman.

She began to realize these weren’t so much randomly whimsical manifestations so much as strategically placed advertisements. The effect was nevertheless mesmerizing. Beatrix now and then had to remind herself that this was in fact quite a magical place, even if most of the time, nothing all that magical was happening, and when there was, its application tended to be a bit crass.

She looked back down at what she was doing, which was making unsuccessful attempts at healing Grant’s wounds. Grant, too, was looking skyward, but with a more pointed objective. With one hand he pulled on his eyelid, and with the other, gingerly poked about the iris to remove his contact lens.

“Anyway, yeah, it just started getting so frustrating after a while,” Beatrix said, returning to her train of thought.

“Huh?”

“Russet. The way he was acting. He obviously has a serious problem, which is why I came looking for you.”

“Oh. Tell me about it. But believe me, just because you give him his pills doesn’t mean he’ll actually take them. He’s an awfully stubborn fella.” Grant paused to sneer at the small malleable lens stuck to his fingertip. “I think these things are shot. They’re filthy. It’s a shame he’s not around. Cleaning things magically is sort of his specialty. I’m afraid I’d just butcher the prescription in the process.”

Beatrix strained her face as she made another futile effort with her ring. “Damn. I’m still not having any luck with healing magic. I guess there’s another way Russet would be useful now. If he were feeling better, I mean…”

“Don’t worry about it. I‘ll be alright,” he said, poking at his sore ribcage.

She reclined, relaxing on the deck of the ship. The cacophony of busily flapping sails overhead was hard to ignore. Through the racket was the giggling of orphans and the various noises particular to a living can of soup. The three were playing some sort of game on the other side of deck, and even from a distance it seemed clear the children were having trouble getting the soup to understand the rules, or anything not soup-related for that matter. To the other side was Nemoira, leaning against a rail. She watched Beatrix and Grant with a sullen expression.

“Why is she looking at us like that?” Beatrix whispered to Grant. He shrugged, still preoccupied with his contacts.

“My apologies,” Nemoira spoke up. “It’s the curse.”

“What?”

“I believe you both share the curse of the Mobius Slipknot.”

Grant stopped what he was doing. With one stinging eye shut, he glared at Nemoira. “What do you know about that?”

She was silent for a moment, reluctant to continue. She then explained, “It is a type of locket, of complicated design and purpose. When assembled and wielded improperly, as I suspect it was, it can have effects on the memory.”

“What kind of effects?” Beatrix asked.

She turned to look at the ocean. “If you can’t remember, then you may surmise the answer yourself. It’s probably best you don’t know, anyway.”

Beatrix found her instinct to remain quiet on the subject overwhelming. But as she ruminated on the locket, and her resolution to be more forthright about things, she found the gumption to confess. “I… I think I have this… Mobius Slipknot. Or, part of it at least.”

Grant’s look of surprise was compellingly genuine. What his face could not conceal, though, was his intense interest. “You do? Where?”

“It’s back at Crossnest, somewhere safe. Actually, to be honest, this was the other reason I wanted to see you. I thought you might know something about it.”

“Maybe.” He stood up, and said as casually as he could through his wince of discomfort, “I’ll take a look at it when we get there.”

“It should be no time at all,” Nemoira said. “We’re here.”

Off the bow, a rocky landmass approached. The ship neared a cave entrance.

Grant frowned at his used-up contacts, then flicked them into the ocean. With little pleasure, he pulled from its case a pair of stylish black-rimmed glasses. He put them on with no less trepidation than if they were the mandatory goggles preceding a punitive pie to the face.

After spending hours wondering if he was getting lost in the unpleasant castle, Herbert was now sure of it. The room was a dead end in his fruitless search. It was a cramped hovel with a low ceiling. Just a sliver of daylight pierced a murky window. Bowls and plates supporting ancient food products covered the floor. Crates of miscellaneous knickknacks teetered on heaps of dusty old furniture. It might have served as a storage room, or a garbage room, or both.

Or, Herbert suddenly thought, it might serve as a bedroom. In the corner was a damp mattress, with one rumpled sheet and an uncovered pillow. Judging by the torso-shaped depression, it looked recently used. Herbert became wary. He looked around, his assessment of the room becoming more of precaution than curiosity.

He backed into a crate, jangling its wares. Something familiar caught his eye. It was a ceramic frog atop the crate. He was sure he’d seen it before. Other items about the room were familiar as well, such as a crystal swan on a nearby shelf, and a broken cuckoo clock on the floor. He’d be damned if that “2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney: Women’s Gymnastics Competition” DVD didn’t ring a bell, too.

He became aware there was someone in the room with him. This awareness was mostly experienced in the nasal passages. He dropped the DVD case.

The cheerful voice spoke. “Ah! A fellow patron of the female athletics. A firm thigh and supple rump are guaranteed to stir the competitive spirit, don’t you agree?”

The strange remark was accompanied by a number of agile motions from a pair of unkempt eyebrows, and a quantity of winks not usually attempted by someone who hadn’t recently suffered a stroke.

Herbert’s open mouth slowly became a thin, irascible line.

“Thundleshick.”

Russet’s slouch was so pronounced, the end of his cape mopped the floor of the corridor. It had been hours since he’d heard from anyone in the fort. Had they all ditched him? Was his company really that difficult to bear? Such rhetorical questions were the bread and butter of those practiced in the art of self-loathing. He shook his head viciously and made swatting motions at his hair in a seemingly involuntary act of repudiation.

Even Carmen was nowhere to be seen. But then, no one was really sure where she lived in this labyrinthine facility. For such a vivacious personality, she guarded her privacy well. He shuffled in the direction he surmised might hold her quarters, but wasn’t holding out much hope.

Behind a door, there was a noise. He stopped, and heard nothing. The hair on his neck stood on end.

[Stop. You. Rucksack.] The sounds chimed in his consciousness.

“What?”

[Let me out of this prison. Free me from this tyrannical wench.]

“Hey…” Russet held his cranium. “Get out of my head!” He waited a moment for the voice to resume, but it didn’t. He watched the door with caution. Again, in his mind, there was a swell of thought. A visceral, menacing rumble.

[rrrrrrrRRRRRRRRRR…]

With a yelp, Russet turned and fled.

Thundleshick stooped in front of a greasy oven. He was attempting to peddle some of his legendary toadloaf to a reluctant Herbert. It was a sales pitch well-rehearsed, but never perfected. “Are you sure you wouldn’t care for some? It’s just above room temperature, you’ll find.”

“No thanks.”

“You must be eager to stray from the refrigerated ethnic fare you and your bunkmate chums enjoy. Just a nibble…” He offered a tool that sort of looked like a garden trowel. It supported a quivering helping of the pale material.

Herbert slapped it out of his hand. “Enough with the toadloaf business. Why don’t we just cut the crap.”

Thundleshick was startled by the outburst, and made a face like he just sat on something that could pop the tire of a monster truck. Herbert went on.

“I don’t like you. You’re some kind of repulsive, magical old man. Okay, so maybe you’re not a wizard. I don’t know what you are. Maybe you’re just a pompous bum who thinks he’s better than everyone else, and who thinks he can keep children hostage for as long as he damn-well pleases, chuckling to himself in his stupid castle like a stupid, smelly jerkoff. What kind of summer camp is this? Where do you get off? Who do you think you are?”

Herbert paused to catch his breath, reddened by his tirade. Thundleshick stood speechless, with a kind of fatherly sympathy in his eyes, as he twirled a bit of his moustache hair between his fingers. Herbert composed himself.

“Anyway, I’m sorry. I just had to get that off my chest. I’m not here to make friends, or kiss your ass, or anything like what all the other campers probably do. I’m here because I just completed like fifty of your idiotic quests, and by my understanding, this more than entitles me to go home.”

He tossed the limp pillowcase into Thundleshick’s arms. As the campmaster peered inside, an expression of unadulterated, childlike glee spread over his face like a rapidly advancing fungus. He was so happy, he began to weep. And then he laughed.

“Boy, this is tremendous! How ever did you collect so many?”

“Well,” Herbert said, dusting off his embellishment cap. “It wasn’t easy. You have no idea how many snoodleflips and blungthumpers I had to shoot to collect those. It was pretty gruesome.”

“This tickles me to no end. Boy… Wizardy Herbert, you must surely have had a wealth of wisdom in your upbringing. I feel I too have been touched by the sagacity of your parents.”

“Yeah, they’re alright, I guess. So what do you say? Is this gonna cut it?”

“Oh, yes, yes, my word. I should say all this entitles you to a stiff reward indeed. One moment…” Thundleshick was suddenly a blur of effluent elderly energy. He scurried to the other side of the room. In his excited haste, he bumped into Herbert, nearly knocking him over.

“Oof… hey, careful.”

Thundleshick’s busy hands upset piles of junk. Herbert quizzically observed the furious search. “Hey, what are you doing? Can’t you just, you know, wave your wand, or do a dance, and just transport me home? What are you getting there? Something like a… shooting star I ride back to New Jersey?”

“Yes! Yes!! Ah-ha, here it is, here it is! Been saving it for an occasion just as this one. I only hope you appreciate the amenity as much as those of us for whom chronic nether-regional chafing is a maligned way of life.”

Thundleshick beamed as he presented him with the hefty 24-pack of Charmin double-quilted toilet paper.

The Rubicund Wayfare bobbed through the rough waters of the cave passage. The waves were loud in the narrow tunnel, but became silent when the space opened more generously into a cavern. The water was calm, almost like glass, and in the center was a statue. Its pose appeared designed to roust the passions of a patriot, while its face wore a certain severity, the kind ensuring commitment to political and militaristic resolve.

Nemoira stood on the bow, pointing her telescope toward the statue. A beam of light projected from the lens. The statue began to glow, and then turned deep red. The subterranean lake bubbled. The surface of the water lowered.

In Fort Crossnest, a low gurgling sound filled the great chamber labeled “Уровень 37” in weathered paint. The wide circular opening in the floor began to overflow with dark, foamy water. The water level rose to match a hazy line of scummy demarcation on the wall.

From the large tunnel in the chamber, opposite the entrance to the rest of the fort, the ship sailed in.

Herbert was waiting for the punch line he knew would never come. Irony to this man was likely as distant a stranger as a hot shower. Herbert’s eye made fierce stabs at the toilet paper, and then at Thundleshick’s beaming face. His hand drifted toward his sidearm. Thundleshick’s puffy, smile-bolstered cheeks appeared to deflate.

“What’s wrong, boy? If you’re worried I’ve been too generous, think nothing of it. Your valor has been proven beyond question.”

Herbert took a step forward, scowling poisonously at the awarded toiletry. Thundleshick’s eyes moved back and forth, as if following a schizophrenic pendulum.

“Hmm… Boy, this is not the first time you’ve encountered such a luxury, is it? You wouldn’t need… a demonstration of its use, would—”

“No, I sure as hell wouldn’t!” Herbert backhanded the soft, bulky package. It skidded to a stop nearby the small mound of jiggling toadloaf. “Now give me the real prize. I know you can get me out of here. I know you’ve got… powers.”

Thundleshick’s face spread into the smile of a complacent sage. A smile that typically concealed wisdom, but in this case, likely only concealed centuries of dental misery, and wads of meat so large and so old, one of them might be pointed out by a tour guide as the birthplace of a famous 19th century poet. “Ah… I see. I shouldn’t be so surprised to find such pluck in your spirit. Then it’s more you want!”

“No, I don’t want more. I don’t want any Kleenex, or a bottle of Toilet Duck, or any Depends adult undergarments for that matter. I just want you to please… send… me… HOME.”

Thundleshick placed a brown, turd-like finger to his lips and became pensive. His eyes twinkled with a realization. “You… still haven’t seen yet?”

“What? Seen what?”

“Yes, your vision is still impaired. It’s plain as day.”

“What are you talking about?” Herbert became conscious of the eye patch pressing against his left eye socket. He reached up, as if to touch it, but his hand quickly dropped again to the vicinity of his sidearm.

“I believe I have just the thing.” Thundleshick groped within his grisly tunic, producing a small vial. It looked like something a medieval apothecary might keep in great supply. “Take this, young Herbert. It will help you see again.”

Herbert’s livid hand snatched it away. He approached the campmaster, becoming more agitated with every gift that had nothing to do with transportation to his house, or at least somewhere in the tri-state area. “I can see just fine. I don’t need one of your bogus remedies or stupid elixirs. My eye patch doesn’t bother me, and it’s my business anyway. Now are you going to send me home, or is this going to get ugly?” Herbert’s hand unfastened the securing strap of the holster, and settled lightly on the gun’s grip.

Thundleshick took a step back, his brow wrinkling with wretched folds of intimidation. He dwelt on Herbert’s bullying tactics, which were enough to cause even a powerful magician to freckle at the advance of a slightly-built, temperamental teen boy. But then, Thundleshick’s natural cowardice wasn’t to be overlooked, nor was the powerful weapon clinging to the boy’s hip.

“I… I believe I can arrange some sort of transport accommodation,” Thundleshick stammered. “Could… could you just take a step or two to your right?”

Herbert immediately looked at the floor to his right. “You mean you want me to stand over that little trap door? You must think I’m a complete id—”

“You might want to tuck and roll at the bottom.” Thundleshick’s smudgy sausage-fingers twiddled furiously as if playing a tiny piano. The small hatch swiftly relocated itself beneath Herbert’s feet. There was the sound of wooden shutters snapping open. Everything went dark.

Beatrix climbed one of the many staircases in the jaundiced, ever-flickering light of Fort Crossnest. She was nervous about seeing Russet again. Who knew what he’d gotten himself into while she was away. But whatever trepidation there was, her excitement outweighed it. She was happy to be helping him.

“Grant?” she asked, sort of sheepishly. “Do you think I could take a look at Russet’s medication?” Was it petty of her to want to be the bearer of good news? She didn’t know. After all, she was the one who went to the trouble of getting it for him. Grant handed it over without a word about it.

Higher up, Russet moped through the corridors, massaging his head. The voices had subsided for now, but only served to leave his own tormented inner voice with the stage to itself, chewing the scenery like an off-Broadway ham. Shouldn’t Beatrix have returned by now? She must have washed her hands of him completely, and he couldn’t blame her. He wished he could have seen her at least once more before she disappeared from his life.

He leaned against a wall and slid down to the floor. He took out his wand and gave it a bored examination. He played with it farcically, sneering, as if lampooning an effete orchestra conductor. In his current state of mind, he’d have better luck cajoling magic from a toilet brush (a non-magical one, at least). He felt like an idiot when he thought about his prior gusto with magic, and the way he behaved in general during his fits of exuberance. It disgusted him. Only a complete jackass would act like that. He threw the wand down the hall.

A hand picked it up delicately. The corner of Russet’s mouth turned upward slightly. Beatrix smiled back.

“There you are,” he said. “It’s been… well, I’d lost track of how long!”

“Hey, Russet,” she replied. “Yeah, I was gone for longer than I…” She trailed off. Russet was on his feet, approaching with a wide grin. The closer he got, the more apparent it was he was not looking at her, but a step or two to her left. The place where Grant stood.

“Hi, buddy. Good to see you, finally,” Grant said wearily, but with a sincere smile. Russet threw his arms around him for an impromptu brotherly hug. Grant returned the gesture, or maybe humored it, as he glanced at Beatrix with look of mild embarrassment.

“Um…” Beatrix began, feeling taken aback by the reception. “I have your pills… if you want them.”

“Oh. Many thanks, Bea!” His shimmering eyes flashed at her, then returned to Grant. The two of them were already striking up an animated conversation, presumably as if they’d never parted. Lack of medication aside, Russet appeared to be in a better mood already. As much as she wanted to think so, it was hard to believe this development had anything to do with her.

Herbert felt like he was walking through a poorly kept zoo. The sounds of agitated creatures filled the cavern-like room, a place he assumed was a kind of dungeon. A very loud dungeon.

The menagerie’s hootings only became emboldened as the fittest systematically conquered and consumed the weak, and celebrated with the triumphant swelling of throat sacks and flaring of proboscises. Over there, a baboon postured over the broken frame of some kind of iguana. And sitting there atop a suitcase was a beefy tomcat washing itself nearby the remains of something that was optimistically a rat, but more realistically was a Chihuahua judging by the collar.

There was a substantial heap of suitcases and backpacks in which the beasts burrowed tunnels and built whelping nests for their young. Herbert began to suspect it might not be a dungeon so much as a luggage room. And then again, it might not be a luggage room so much as a place serving as dumping grounds for an overabundance of goods confiscated from mistreated children.

This notion gained further plausibility when he encountered a navy blue suitcase. It was the very one he’d surrendered to a helpful simian paw only a few days ago, just moments before being persecuted by large skeletons.

Herbert’s heart sped up. There was nothing special in it of course. It was hard to get bent out of shape over parting with a few pairs of socks, and a few reluctantly-purchased tools of the accounting trade. But there was one thing, something he’d thought he was glad to be rid of once and for all. Now, though, his thumping heart suggested otherwise.

He crouched to unzip the suitcase, but noticed he was still clutching the vial thrust into his hand by Thundleshick. He stood up and put it into his jeans pocket. He made a face, feeling around inside the pocket, then checked the other one.

The doll was gone. The bastard picked his pocket.

Herbert looked up into the great, dark void, unable to detect a ceiling, let alone the trap door from which he fell. Who knew how long it would take him to get back to Thundleshick’s chamber from here, or if it was even possible in this architecturally capricious castle. There had to be another way. Indeed, from a distant source there was daylight, perhaps an exit to the swampy castle surroundings. At least he might be able to start again from the main entrance.

He sighed, and sifted through the contents of his luggage. He tossed aside a small pocket ledger, moved a neatly folded pair of underwear, and with both hands, hoisted an antique adding machine, once belonging to his great grandfather, over his head onto the floor behind him, where it broke apart noisily. He stopped.

There it was.